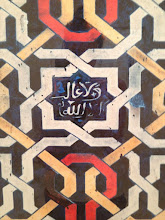

I have come to the conclusion that blogs are entirely too easy to start and therefore far more difficult to keep up. Like pets, or flowers. Needless to say, I am delayed on my next entry since I have procrastinated far too much on an application for a conference in the Fall at which I *hope* to present my research from the year. I intend to finish the entry this weekend, but just to give you a little sample of what I will ramble about, I'll let you ponder these images below.

Voilà. Pondered enough? So its mother’s day in America—in France, my adopted homeland, it isn’t for a few weeks: you know how the French love to take their time on everything. Unfortunately for me, another entry is long overdue so I am submitting this entry on and for mother’s day à l’americaine, and not for the French counterpart. I am consecrating this article both in part to my own mother and by extension to everywhere. I am not usually this sentimental, but in realizing a few days ago that I would need to call my mother rather soon to thank her for having me, I had the idea of using an example of her work for Juxtaposition. My next thought, then, was what to compare it to. You of course know what I finally chose and may already have a good idea as to why she was a good choice.

The example I selected of my mother’s shown above is emblematic of her style both now and of years past. The bifurcate, almond shaped motif can be found throughout many of her most recent works. It is manifested in sizes large and small, in formats 2D and 3D, and from a variety of mediums. And contrary to popular belief among those who have seen an example of one of these, it is not a vagina.

As I see it (both as the daughter and the art historian to be) this form is the evolution of an abrupt burst of melancholic inspiration after the death of my father in March of 1996. Very soon after, perhaps even before the end of that calendar year but my memory likely fails me here, my mother was diagnosed with the same kind of malady that her husband had so briefly suffered from. She was however fortunate enough to keep on living in exchange for the removal of several lymph nodes surrounding the important sentinel node, in addition to the malignant tissue plaguing her. I regard these two events as two pieces of a whole, much like my parents before my father’s death, whose cruel proximity only intensified each other’s effect.

It is thus not surprising that such a change be reflected in her work. Her art changed from being composed of slate, plaster and stone, to lighter mediums such as muslin, paper, and glue. This evolution also demonstrated certain physiological needs: the lack of those precious lymph nodes rendered my mother incapable of being able to lift the heavy material that once so defined her immense works of art. So she adapted. She started anew with shapes that resembled corpses—-suggestive of death—in some forms and cocoons—suggestive of life—in others.

Her works from this époque range from a series of identical wall pieces, to a family of three meant to be admired outdoors, to macabre floor sculpture that lay draped in diaphanous layers of silk.

It is this shape that first appeared very much to resemble a human-like form that has become that which you see in examples like Looking for Tomorrow. In these past fourteen years this motif has been stretched and compressed and squeezed and pulled into almost every variation available. Beginning in 2005 it was the repetitive motif in a long scroll-like drawing for which every manifestation of this shape represented one fallen American soldier in the was in Iraq. Here these shapes take a particularly morbid, though appropriate, greater representation as they had in their early stages.

But in other forms, such as the exampled image above, they resound with hope and life. This form is circular thus cyclical like the cycle of life, or you could say oval, like an egg, a natural incubator of life.

Now when I reflect upon her work I think about artists like Sol LeWitt who essentially used the same aesthetic tools throughout many periods of his career, he simply changed certain parameters, which allowed him to created an entirely different work. I believe—and I could be completely wrong about this, among our many mother daughter conversations, the greater message of her art is seldom the principle topic—that my mother could be endeavoring to perform a similar experiment. To exhaust the applicability of this motif among other shapes, different colors, in different sizes and with different meanings. I cannot reason to validate the hasty speculations of others of this developing motif as representative of va-jay-jays. Get your minds out of the gutter!

Wall Drawing 999 : Parallel Curves

Sol LeWitt

2001

Though let me be fair. This is not the first time that viewers have admired a given painting, or group of paintings even, and delighted to conclude that the subject at hand was vaginal. Perhaps the most famous among this group of accusés is Ms. O’Keefe. This artist is admittedly far from my area of expertise but in my own musings I have come across interpretations of her work that attest to this fact. Such is also apparent in viewing the vast range of works she produced. She was not limited to only painting close-ups of the stamen and pistell of flowers.

Ram's Head White Hollyhock and Little Hills

Georgia O'Keefe

1935

Oil on Canvas

The Brooklyn Museum

In the late 1920s, for example, feeling the need to travel and experience new lands, the young artist moved out West from New York to New Mexico where she lived for at least for part of the year until 1949, but would always return to New York in the Fall to be with her husband Alfred Stieglitz. She would eventually settle there permanently after his death and remained there for the rest of her life. From the decades she spent in New Mexico, her artwork clearly shows how used her environment and thus her personal life as inspiration.

We often try to simply an artist's style into one particular word or phrase as a means to understand him or her better. Claude Monet: water lilies. Degas : ballet dancers. Robert Ryman: white on white (that one is for my dear mother), etc. But it is really only in looking at their works as part of a whole, as a dynamic component of a continuum, that style can judged and labeled.

And not to let anyone down who read the sneak-peek to this entry and got all excited about one subject in particular, this one's for you. There are, please be assured, plenty of artists that create art with the express purpose of celebrating the Origin of the World. Though, Courbet too, please bear in mind, did not dedicate his life to such portraits. He resisted the title, but is donned nonetheless, as the father of Impressionism. This is simply commission that created enough controversy to mark his career.

Gustave Courbet

Origine du Monde

1886

Oil on Canvas

Musée d'Orsay

ahhh.

ReplyDeleteYou'll like this, maman, I promise.

ReplyDelete